Joseph Anton Koch

The Wetterhorn, 1824

Joseph Anton Koch

The Wetterhorn, 1824

Kunst Museum Winterthur, Stiftung Oskar Reinhart, Ankauf, 1950

Foto: SIK-ISEA, Zürich (Philipp Hitz)

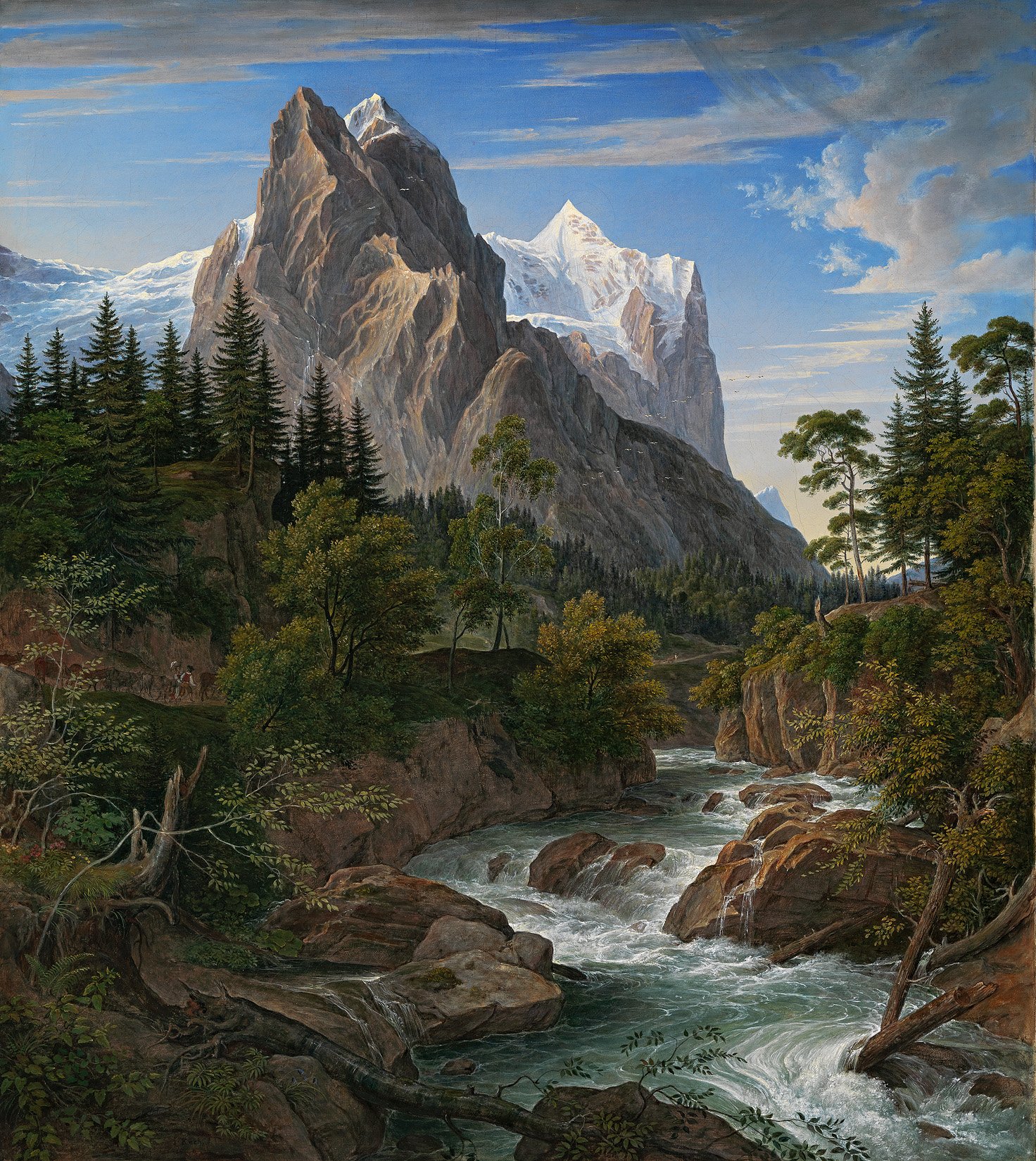

Originally from the Tyrol, Joseph Anton Koch spent most of his life in Rome, where he became the head of a German artists' colony. In his paintings he studied not only the Italian Renaissance intensively, but also the works of the important landscape painter Claude Lorrain. Through this preoccupation he soon developed a completely new conception of landscape painting and with it became a role model for a whole generation of young artists. His so-called «heroic landscapes» were in direct opposition to traditional veduta painting and, unlike the latter, did not aim at a lovely idyll, but showed nature from its eerily beautiful side – or as it was called in contemporary philosophy: the sublime.

Before Koch emigrated to Italy, however, he stayed in Switzerland for a long time, living in Basel, Biel, and Neuchâtel, among other places. In 1794, he traveled to the Bernese Oberland, where he created numerous nature studies of waterfalls, mountain peaks and glaciers. Throughout his life these served him as a source for his alpine-themed paintings. Although the Roman-by-choice was primarily concerned with the southern Italian landscape, the Alps also remained an important topic in his work throughout his life. And so, in 1824, at the height of his creative powers, he painted the Wetterhorn.

In this painting, we can see all the elements of a «heroic landscape» being applied: Through a richness of detail and extreme sharpness the painter brings the imposing mountain range close to the viewer. All three zones of the picture are so strongly worked out that even the Wetterhorn – actually in the background – takes on an extremely strong presence, which is almost physically tangible. The seemingly unconquerable nature, full of dense greenery, rugged rocks and dead trees, shows hardly any traces of human civilization – only at second glance does one discover the peasant couple on the left and the tiny figure in the center of the painting. Their vanishingly small size makes the harsh wilderness seem even more monumental. Both mountain and nature seem beautiful and forbidding at the same time, they make us marvel and shudder simultaneously – this is the sublime of nature, this is the «heroic landscape».