Piet Mondrian

Composition I, 1930

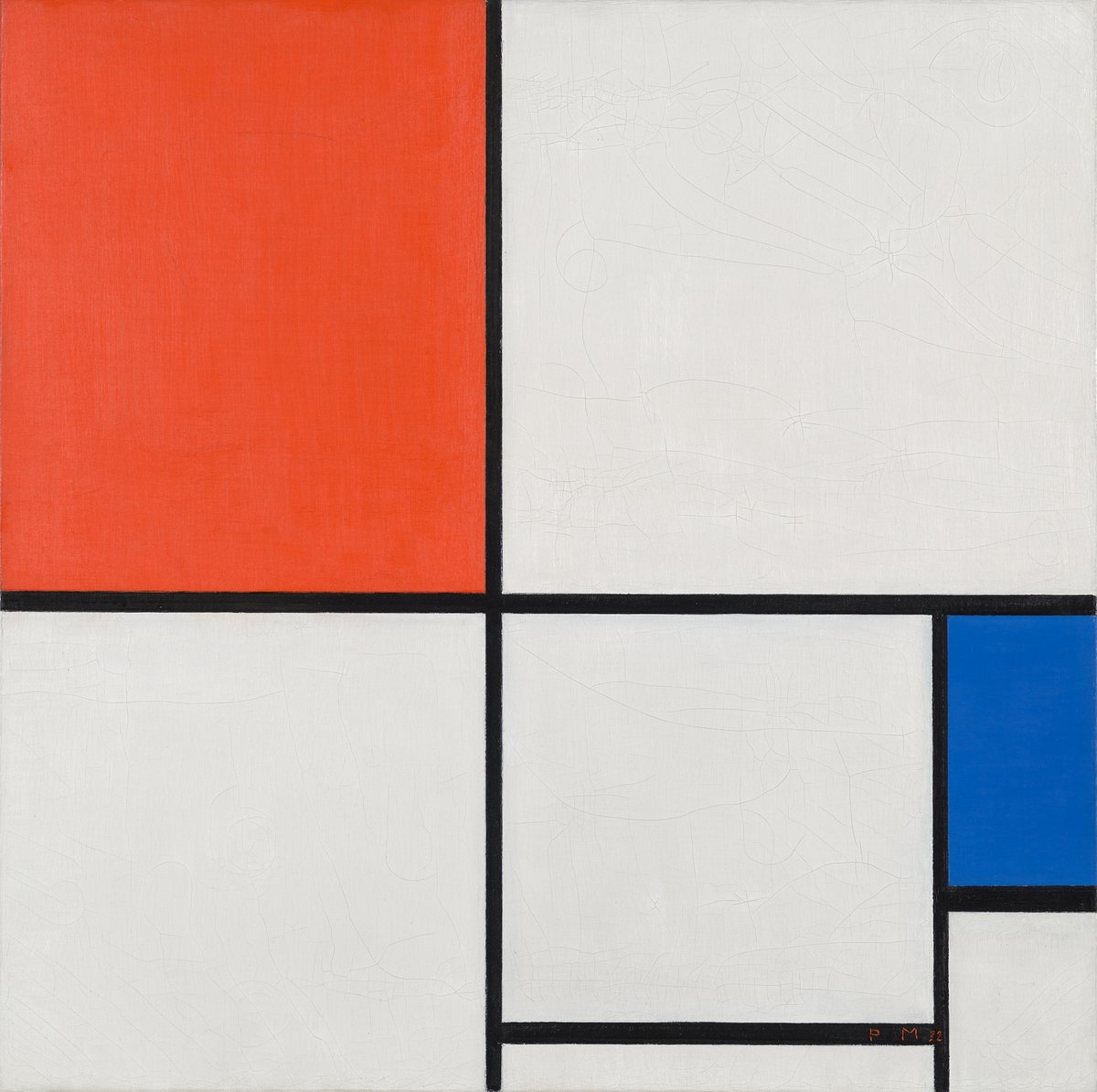

Piet Mondrian

Composition no. I, 1930

Kunst Museum Winterthur, Legat Dr. Emil und Clara Friedrich-Jezler, 1973

Foto: SIK-ISEA, Zürich (Martin Stollenwerk)

Piet Mondrian is the epitome of the abstract painter. He cherished the term, “abstract“, which to him was the fundamental and the universal quality of art untrammelled by detail that could give expression to the deepest, underlying structures. Thus, Mondrian didn’t regard himself as a Dutch painter either. He chose to work in Paris, the capital city of international avant-garde.

The two pictures in the Winterthur collection dating from 1930 and 1932 demonstrate this fundamental style that Mondrian employed. It is the visible qualities of the pictures: Mondrian used the primary colours red, yellow and blue, and they are placed in contrast to the non-colours of black white and grey. The segments and the horizontal and vertical lines constitute further opposites.

Mondrian’s pictures weren’t supposed to have a centre, or a ranking order. He gave every element its counterpart: thus supplying the composition with balance and harmony. Mondrian was aware of the danger that harmony could become schematic, and he therefore worked on schemes to break it.

The picture with the yellow square is an example of this. Do you see identical squares? Well, if you look more closely you’ll see that they are all slightly different. The placement of the yellow is somewhat eccentric. It almost brings the composition out of balance; but the large square balances the yellow out.

Piet Mondrian

Composition A, 1932

Kunst Museum Winterthur, Legat Dr. Emil und Clara Friedrich-Jezler, 1973

Foto: SIK-ISEA, Zürich (Martin Stollenwerk)

In the picture with the red and blue squares, the balance has been altered: the segments are now clearly different in size. The eye jumps diagonally from one colour to the other and from the large white square to the smaller squares.

Mondrian didn’t regard balance as static. He wrote that balance had nothing to do with, “an old gentleman in an armchair or of two equal sacks potato on the scales.“ His harmony was meant to be dynamic, like the harmony in his beloved jazz music.